IN A SEARINGLY HONEST AND EXCLUSIVE INTERVIEW AHEAD OF HER

FIRST SOLO EXHIBITION IN THE UK, ISABELLE VAN ZEIJL TELLS MUTUAL

ART ABOUT HER JOURNEY OF TRANSFORMATION, AND HOW USING A

PARTICULAR ‘BUTTERFLY ORCHID’ HELPED HER DISCOVER THE ESSENCE

OF HER TRUE SELF.

Isabelle van Zeijl, She Is

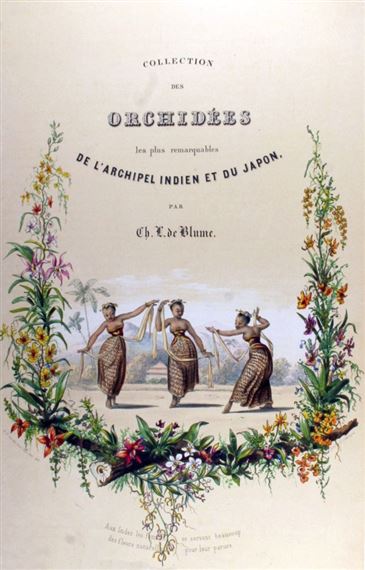

In 1823, the aptly-named German-Dutch botanist, Carl Ludwig Blume, left his home in the Netherlands to explore Asia and carry out extensive studies of Javanese flora. His work was entangled in the many branches of Dutch colonial enterprise, and also in funding disputes with King Willem I.

Java was, at the time, a Dutch colony, and colonial funds were often kind to botanists wanting to scour the Asian reaches of Holland’s occupying arm. But Caspar Georg Carl Reinwardt, Blume’s predecessor as director of the botanical gardens at Buitenzorg (modern day Bogor) had run afoul of the King, as his Crown-funded cataloguing of Asian species of flower had not returned enough capital to The Hague. Blume assumed the position of director of the garden in 1823 with some confidence, but it proved misplaced. Funding dried up, and the garden closed in 1826.

Blume’s journey was not entirely fruitless, however. His Catalogus van eenige der merkwaardigste zoo in-als uit-heemsche gewassen te vinden in’s Lands Plantentuin te Buitenzorg arrived back in The Hague, sent from the Indonesian archipelago, in either 1823 or 1824. Among its detailed descriptions appears the first European cataloguing of one of the modern world’s most popular decorative flowers.

C.L. Blume, Rumphia, Plate 194, showing the Phalaenopsis Orchid

The story goes that Blume, in Java, approached what he believed to be a cluster of brightly colored butterflies fluttering around the branches of a tree. As he moved closer, he realised the delicate, silken things were in fact a distinct and unique kind of flower. No stranger to nominative determinism, Blume named his new find after what he’d thought he’d seen. The Phalaenopsis Orchid takes its name from the Ancient Greek suffix, -opsis, meaning “looking like”, and the word phalaina: ‘butterfly’ or ‘moth’.

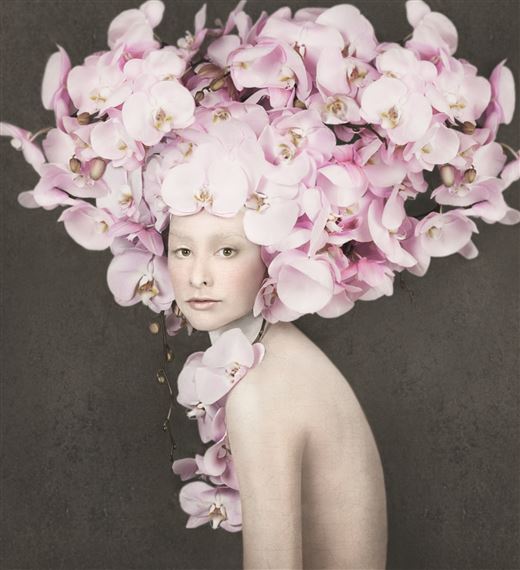

Isabelle van Zejil was also looking for butterflies when she found orchids. Her newest series of photographic self-portraits show her wearing an extraordinary headdress woven from the flowers. Her original vision was to use butterflies. “It was during a difficult period for me,” the artist says, “I was cut off from the world for about six months, going through difficult times. And when I came out I wanted to make a headpiece out of butterflies.”

For many reasons, butterflies were not a suitable material for making the piece. “So then I was looking for a flower, and intuitively I chose orchids. I always pick the elements and materials on an intuitive basis.” Later, when looking up the significance of her chosen material, Van Zeijl discovered Blume’s similar journey. “I thought, my God, I have chosen butterflies!”

Title page of C.L. Blume’s Collection des Orchidées les plus remarquables de l'archipel Indien et du Japon, published by C. G. Sulphe, Amsterdam, 1858

It’s an apt symbol for Van Zeijl’s work, which plays around with the visual language of transformation to chart a very personal kind of self-growth. “The butterfly’s remarkable shape-shifting journey I think carries a very important message, for us, of seeking out our true essence no matter how far removed it may be from our present selves. It teaches us that growth and transformation can be not traumatic or painful but rather liberating and joyful, and a natural part of life,” Isabelle says with zeal.

The realization is hard won. Van Zeijl works from dark places of personal childhood trauma to achieve a form of aesthetic beauty that’s as stoic as it is delicate. “I grew up in an unsafe environment,” she says. “I was exposed to violence, belittling, abuse. This meant I felt the urge to investigate myself very deeply and portray myself.

“Growing up in this unsafe environment, I turned my eye to all that was beautiful around me That became my mask, my protection, my purifier. To overcome all...that shit.

“And also during this time, I was around 16 or 17, I literally lost my voice. I could not speak anymore. I was so blocked by all the violence that I could not speak. I did not speak for months. So I started to speak through my self-portraits.”

Isabelle van Zeijl, photographed by herself

From such personal trauma there grew a preoccupation with things that were beautiful, a logical escapist impulse. For Van Zeijl during childhood, this meant poring through books on Renaissance art and also fashion magazines which she found at home. These early experiences with idealized aesthetic images still very much influence her work today. “These are the layers you can recognise in my work. I have snippets from Frans Hals or Rembrandt, but also from fashion photographers, Kate Moss and other fashion models. I’m highly inspired by Alexander McQueen, of course. He also makes, out of dark zones, these beautiful designs.”

McQueen is an exception - “His models are more like actors!” - but more broadly, the kind of beauty prized by the world of fashion began to trouble Isabelle, particularly because of the emotional anonymity, the lack of autonomy, afforded to models. “It has nothing to do with the person herself! It has nothing to do with the model - what she thinks about how she should look and dress.”

Van Zeijl began to play with this idea of autonomy, the blurring of the subject with the object. As such, she ends up occupying every role in her own process of photography. She is photographer, model, set-designer, director, all in one. In one sense, she’s fulfilling the societally imposed dream of “every little girl” - to be on the magazine cover - but in another sense, she’s making a point about exposure, tenderness, strength, and self-fulfilment.

Isabelle van Zeijl, She

“I play with these elements. Sometimes I take the same fashion poses as these models. But behind that pose is also a lot of meaning, because a lot of my poses are really vulnerable. And vulnerability is, I think, one of the hardest emotions or characteristics to be and to present. We are not taught to be vulnerable. We are taught to be strong. But I think it’s in our DNA that we want to be loved and to belong.”

An important part of depicting this vulnerability, which is itself an important kind of strength, was the incorporation of the orchids, moving her portraits from involvement with the contrivance of textiles to the organics of floral arrangement. Another revelatory element of the process was working with florist, Paul Wijkmeijer.

“I went to a shop and there I met Paul, the flower artist. He said you can’t build a headpiece with the orchid because it’s too delicate, it’s too fragile. I said yes, but I will.” Despite his misgivings, Wijkmeijer was taken with Van Zeijl’s determination, and agreed to work with her. “Two days later, he came into my studio, and this was the first man to enter my studio. To see my vulnerability. He literally saw me naked, so it took courage to invite him in, but if it wasn’t for him, I couldn’t have taken the risk of building this headpiece! In the end it went organically, we did not manipulate the flowers. There are over four hundred orchids in this headpiece.

Work being done on the orchid headpiece

“In the orchid there’s a lot of meaning. It’s the most delicate flower but it also represents love, unity, and strength.”

Opening herself up in this way, budding and blooming through vulnerabilities, organic visual languages, and the difficult but fruitful act of collaboration, has helped Isabelle attain new heights of personal expression and artistic success.

Isabelle van Zeijl, Own

“When I tell people that story, they open up and feel the need to tell their own stories, and that’s very inspiring! And that’s nine out of ten times why people buy my work. And that’s the biggest compliment. That they not only buy it because of the creative reasons but really for the reason that it empowers them. Defining and speaking your personal truth, embracing all that you are...I think that is really living your own truth. And that’s true beauty.”